Libya’s Power Struggle: Who Controls What in 2025?

A Nation Divided

More than a decade after the 2011 uprising that toppled Muammar Gaddafi, Libya remains a country without a unified government. The promise of democracy quickly gave way to a series of transitional governments, foreign interventions, militia takeovers, and failed elections.

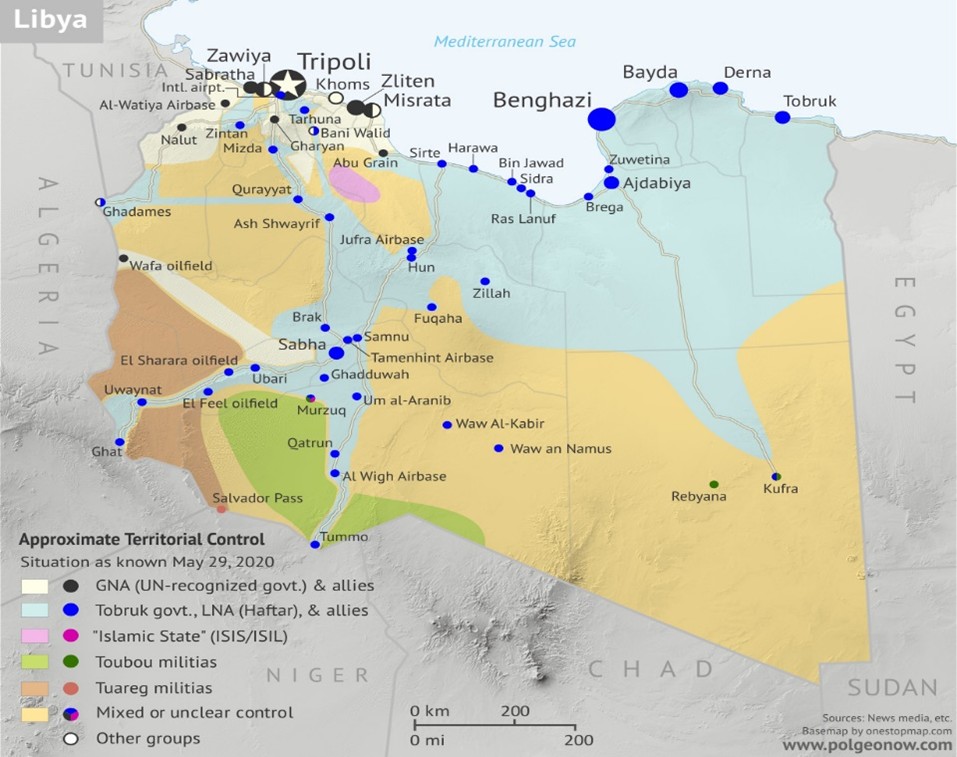

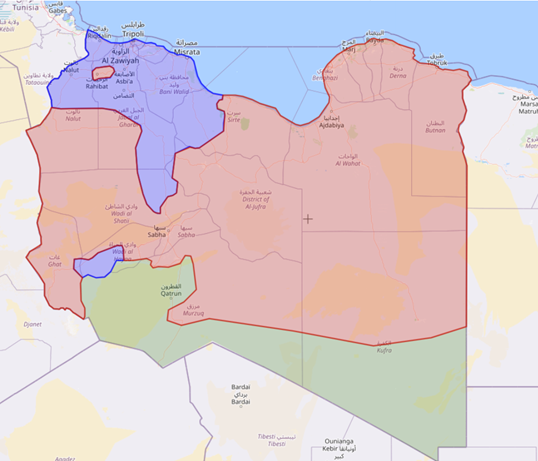

During this time, the rise of jihadism with groups like ISIS further complicated the situation, leading to increased instability and violence. The 2014 civil war created two parallel governments – one in Tripoli in the west, and one in Tobruk in the east – setting the stage for the political divide that persists to this day.

In 2021 (less than a year after a ceasefire that brought about some calm), the UN facilitated the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU), headquartered in Tripoli and led by Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, with the goal of preparing the country for national elections. However, delays and disputes over electoral law caused the vote to collapse.

In response, the House of Representatives (HoR) in the east appointed a rival administration – the Benghazi-based Government of National Stability (GNS) – backed by General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA).

As of today, the country remains divided between these two power centers, each supported by a patchwork of militias, foreign allies, and economic levers – mainly oil.

Government of National Unity (GNU) – Tripoli

Led by Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, the GNU is still recognized internationally as Libya’s legitimate (but provisional) government. It was formed as a merger between the civil war-era interim Government of National Accord (GNA) and the rival Tobruk-based government (Second Al-Thani Cabinet). The GNU governs from Tripoli but depends heavily on an unstable alliance with powerful militias to maintain control.

Key fighting factions aligned with the GNU include:

- 444th Brigade (led by Maj. Gen. Mahmoud Hamza)

- 111th Brigade (commanded by Abdul Salam Zobi)

- Stability Support Apparatus (SSA) – formerly led by Abdel Ghani al-Kikli (a.k.a. “Ghneiwa”), who was assassinated in May 2025.

Ghneiwa’s assassination triggered intense clashes in Tripoli, killing at least six and exposing the fragility of the GNU’s hold on power. His death left a power vacuum in the Abu Salim district, sparking infighting among rival militia groups vying for control.

Despite these challenges, the GNU retains international legitimacy, especially from the UN, Turkey, and Qatar. However, it has drawn criticism for delaying elections and entrenching a system dominated by militia networks and corruption.

Government of National Stability (GNS) – Eastern Libya

Headquartered in Benghazi and backed by the HoR in Tobruk, the GNS is led by Osama Hammad, with the real power residing in Khalifa Haftar, commander of the LNA and de facto leader of eastern Libya. Haftar has ruled the region with a military dictatorship since 2017, distancing the nation’s eastern faction from international support and recognition, namely the West. The GNS claims the GNU’s mandate expired and argues that it is the only legitimate authority left.

The GNS has the support of Egypt, the UAE, and Russia, and controls most of Libya’s oil-rich interior and eastern coastline. However, its push for broader recognition has been hampered by its association with Haftar’s past military offensives and war crimes allegations.

In May 2025, the GNS escalated tensions by threatening to declare force majeure on oil fields and export terminals – a legal tool used to halt production and contracts. The move followed alleged attacks on the National Oil Corporation (NOC), which the GNS blamed on western factions. The NOC, which remains based in Tripoli and dominates the nation’s energy sector as a state-owned entity, downplayed the incident as a minor localized dispute.

This recent development can be seen as a direct consequence of Libya’s fractured landscape. The ramifications are crucial, as oil remains Libya’s main economic source. The NOC is one of Libya’s most internationally prized institutions, attracting more foreign attention than any enterprise in the nation. No other entity in Libya is capable of dealing with foreign firms and sovereigns while generating substantial revenue for the country’s economy.

Militia Rule and Urban Power Struggles

Militias are arguably the most powerful actors in Libya. In Tripoli, they operate as quasi-governmental forces, receiving salaries and benefits through state institutions while operating autonomously.

The recent assassination of SSA chief al-Kikli (Ghneiwa) has triggered friction among western militias, with gunfights breaking out after the killing involving both the SSA and 444th Brigade. While Ghneiwa was known as a firm supporter of the GNU, it’s notable that his reputation has been marred by allegations of human rights violations.

With SSA’s leader now out of the picture, the possibility of rapid escalation in the densely-populated region now arises. RADA, another Tripoli-based militia, is positioning itself against the GNU while encouraging protests against Prime Minister Dbeibah. While the flammability of the recent developments is debatable, what’s certain is that it further exposes the Tripoli government’s lack of control and ability to maintain balance even within their own domain.

In the east, Haftar’s LNA remains the dominant force. But even there, unity is superficial. Several tribal militias, particularly (but not only) in the southern part of the country, maintain control of their own areas, complicating GNS governance.

What’s Next?

With no elections on the horizon and both rival authorities struggling to properly govern their own areas, Libya’s near-term future is likely to remain shaped by fragmentation and turmoil. The assassination of key leaders, clashes between militias, threats over oil control, and ongoing proxy involvement by foreign powers suggest a fragile status quo.

The recent uptick in violence is cause for concern, but it can also be perceived as a test to see if the nation is capable of internally suppressing escalation and implementing calm. Unless a credible political process is revived, Libya risks becoming a permanent patchwork of competing powers-nominally governed, but effectively ruled by force.