Libya’s Dual Exchange System Undermines Economic Recovery

It’s no secret to Libyans that the economy remains weighed down by the legacy of civil conflict and the persistent division of authority between rival eastern and western administrations. This fragmentation has left the Central Bank of Libya (CBL) unable to enforce a unified policy. For instance, eastern authorities effectively ran a parallel monetary system. From 2016 to 2020 they circulated billions of foreign-printed dinars through the Benghaz central bank branch, which Reuters notes “aggravated economic splits” by creating different exchange rates in the east and west. The Tripoli-based CBL struggled to integrate these notes. By mid-2024 it announced withdrawal of the newly issued LD 50 note to counter the counterfeit [RIVAL] surge in the east. By then the dinar had already begun sliding: early-2024 reporting links the currency’s slump to the influx of these unauthorized notes in eastern markets. These developments illustrate how political fragmentation has directly undermined Libya’s monetary governance.

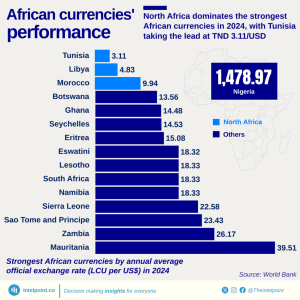

A core consequence has been a vast gap between Libya’s official and black-market exchange rates. Under official policy the dinar was held at roughly LD 4.8–5 to the dollar in 2022-23, but the street rate diverged rapidly. By late 2024, surveys found the parallel rate about 30 to 40% weaker than the peg. For example, IMF data show the official rate at LD 4.8/$ while the parallel market averaged about LD 6.9/$ in 2024. Even after an April 2025 devaluation of the official peg to LD 5.5677/$, the black-market dollar remained near LD 7.20. Such a persistent premium acts like a hidden tax on imports and fuels corruption: those with access to cheap official dollars (through government channels) reap windfall gains by selling them on the black market. The World Bank warns that parallel exchange markets are “expensive, highly distortionary… and associated with higher inflation”, a warning clearly borne out in Libya’s data.

Official inflation statistics have appeared unusually low under these pressures – partly because subsidies and price controls mask cost increases. In reality, Libyan consumers feel much higher inflation. By mid-2025 the UN’s World Food Programme reported Libya’s food-price index up about 8.9% year-on-year, with western regions seeing surges above 20% in the cost of a basic food basket. Those figures reflect the dinar’s weakness and supply constraints: WFP explicitly attributed them to “mounting inflationary pressures” driven by the currency’s decline. Analysts note that Libya’s currency instability – tied to its divided governance – is squeezing household budgets and complicating economic planning. In short, the dual exchange system has injected significant hidden inflation into the economy.

To address this, the CBL and interim authorities have imposed a series of stopgap controls, with limited success. In mid-2024 the central bank tightened dollar allocation: banks were told to ration foreign exchange, import financing was restricted to a short list of essential goods, and a heavy tax (initially 27%, later cut to 15%) was placed on FX purchases. These measures did reduce official dollar outflows. For example, LC-financed imports fell about 6% in early 2024, but mostly by driving demand underground. The CBL even contracted for LD 30 billion of new banknotes (through De La Rue) to ease chronic cash shortages, and it announced the recall of older notes after a wave of counterfeits. In practice, however, these interventions only marginally slowed the dinar’s depreciation on the black market. Salaries and subsidies continued to swell, but banks lacked hard currency; Libyans queued for cash while traders quietly relied on the informal FX market. The official peg held by decree could not withstand these underlying pressures.

International institutions and Libya’s own economists have been unanimous about the remedy: Libya must unify its exchange-rate regime and restore confidence in monetary policy. IMF staff reports repeatedly emphasize that Libya’s recovery will remain fragile under the current dual-rate system. The 2025 IMF Article IV consultation explicitly recommends phasing out the foreign exchange tax and all restrictions, and moving to a single market-based exchange rate. It also stresses that fiscal consolidation and clear governance are needed to back up any reform.

Similarly, the UN’s support mission has called for a single unified budget, observing that agreeing on one national fiscal framework would “strengthen the Central Bank’s ability to implement effective monetary policies and stabilize the exchange rate”. Libyan analysts echo these points. For example, one expert wrote that adopting a unified budget would “provide a clearer picture of total demand” and enable the CBL to compute a true value of the dinar. In short, both international and domestic voices agree: without political and fiscal convergence, monetary reform cannot succeed.

In practice, however, the political obstacles have been formidable. Libya’s split has deep roots. In September 2023 the eastern city of Derna was devastated by floods, diverting political attention and resources. In mid-2024 rival parliaments in Tripoli and Tobruk even came to blows over control of the CBL, briefly halting oil exports and sending the dinar into free-fall.

A UN-brokered deal in late 2024 reinstated a single (technocratic) bank governor, but it did not merge the competing budgets. As of 2025 Libya still maintains two budgets and overlapping spending programs – indeed, the two administrations together spent roughly LD 224 billion ($46 billion) in 2024. This massive outlay pushed domestic arrears to about LD 270 billion, while oil revenues remained the main source of finance. The UN has warned lawmakers to agree “on a framework for spending” with strict limits in 2025, implying that without fiscal unity the dinar’s woes will continue.

The bottom line is that Libya’s economic recovery will remain precarious unless its currency regime is unified and monetary policy made credible. Without a single exchange rate and a trusted central bank, inflation and volatility will persist, and investors will demand a steep risk premium on any Libyan assets. As one IMF report bluntly concludes, merging the dual exchange regimes and eliminating the parallel market premium are prerequisites for macroeconomic stability. Only under those conditions can Libya hope to translate its vast oil wealth into a sustainable recovery instead of watching it seep away through black-market distortions and patronage networks.